They go on to say, "Much of the Department’s work under Secretary Haaland’s leadership also centers on acknowledging the impact that relocation, forced assimilation, and lack of critical funding has on Indigenous communities across the country. We are committed to elevating those issues while empowering Tribal governments and Indigenous peoples."

Agenda:

1. Anti-racism intentions

2. Colonizing New England

3. Pumpkins and pie

1. Anti-racism intentions:

I have enjoyed studying my ancestry over the years, but I'm well aware of the inherent white privilege of this study. This document, Genealogy and anti-racism by Diane Kenaston, asks the question, "So, are there ways for white people to act as anti-racist allies while exploring our own white ancestry?" She could be writing my own thoughts here:"Through ancestors' participation in the DAR, I have family trees going back to the 1700s ---- and the knowledge that the DAR was formed for explicitly racist reasons. Through ancestors' ability to purchase homes, attend institutions of higher education, and transfer wealth to their descendants, I have paper trails. ... Local, state, and federal governments have valued keeping my ancestors’ records and writing down their names. Some of my ancestors benefited from the Homestead Act, in which the U.S. government transferred to white citizens land stolen from indigenous peoples. Even for those who didn’t directly apply for land under the Homestead Act, by migrating to these shores, my ancestors participated in what is known as “settler colonialism” --- deliberately replacing native peoples with new settlers."

This document has some great suggestions for action, including sections on confronting slavery, confronting settler colonialism and homesteading, and confronting immigration restrictions.

So I set another intention:

I intend to find out whose traditional territory my ancestors were on, learn more about the people, history, and contemporary concerns of these indigenous communities, and share that information with my family, because this is one way I can dismantle the systems of racism.

2. The Pawtucket People:

Last week I wrote about the Rev. Ezekiel Rogers, a Puritan who left England to sail to North America in 1638, so as to practice his religion without interference from the King. My ancestors Joseph and Mary (Mallinson) Jewett, and Joseph’s older brother Maximilian Jewett and his wife Ann (Cole) Jewett, Edward and Ellen (Newton) Carleton with baby John, were all in this company.

They arrived in Salem in the fall of 1638, where they remained for about a month, and then moved to settle a spot about 30 miles northwest of Boston, between Newbury and Ipswich. They called the settlement Rogers’ Plantation, but a year later they changed the name to Rowley, this being the name of the old town in Yorkshire from which some of the company had come.

Originally the Town of Rowley extended from the Atlantic Ocean to the Merrimac River, and was laid out so that nearly all of the early houses bordered on the "Town Brook" or one of its tributaries. The land was known to the Indigenous inhabitants as “Agawam,” which roughly translates to “low-lying marshy lands.”

Finding out the real names of the Native People who lived in the Agawam area took some digging. I encountered wide spread stories about Masconomet, a chief or sachem of the Agawam tribe who ruled a sovereign territory called Wonnesquamsauke, which the English anglicized as Agawam. But this is mostly fiction.

I found an article by Mary Ellen Lepionka called, Who Were the Agawam Indians, Really? She says “Agawam” was never the name of any tribe. Masconomet was a Pawtucket (puh-tuh-kuht), and he wasn't the chief of a tribe; he was a sagamore, the hereditary leader (not the same as a chief) of a band of co-residing Pawtucket families related through patrilineal descent (not the same as a tribe). The Pawtucket migrated from their original homelands in New Hampshire’s Merrimack Valley hundreds of years before colonization, and they identified as a whole through their shared ancestry, and their distinct dialect, but they never organized themselves into a tribe.

The Pawtucket were farmers as well as hunters, fishers, and gatherers. They did not live in settled communities, but migrated seasonally throughout their territories in Massachusetts and Rhode Island; they lived in bands of 10-50 people. They spoke a dialect of Western Abenaki, and needed interpreters to talk to speakers of Massachuset, including the Wampanoags. This doesn't mean that the Pawtucket were isolated; in 1620, following European contact, Abenaki-speaking groups allied together through the Pennacook Confederacy, named after its most powerful group. So, the Pawtucket were connected in a vast network of sophisticated, nuanced, ever-changing relationships of kinship and alliance.

When asked who they were, the Pawtucket had simply given the name of where they were at the time - their place or village. The Europeans misapplied those names to invent tribes where no tribe existed - the Agawam, Naumkeag, Wamesit, Pentucket, Nashua, Wachuset, Weshacum, or Mystic Indians: They were all the same people, and most likely referred to themselves as “the people” (Ninnu) or “the people here” (Ninnuok).

The people that the settlers met were the survivors of a population that once had been numerous. In the late 1500s, the native population in New England may have been as many as 12,000, but 90% of the local population had died in the early 1600′s from a pandemic - likely outbreaks of both small pox and hepatitis - brought by contact with Europeans.Much of the confusion likely came from the intermingling of those few Indians that survived this pandemic. They no longer had clear lines of lineage or defined territories; these were small groups of people of many tribes, banding together to survive. And then rival Northern tribes swept down to attack the survivors. Some stories suggest that Sagamore Masconomet invited the English to settle as protection from the Northern tribes. I don't think the English waited for an invitation! In any case, on June 8, 1638, Masconomet - the last Sagamore of the Pawtucket - signed over all the land under his control to John Winthrop Jr., representative of the English settlers of Ipswich.

In the 1830s Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act resulted in the forced migration of Indians to areas west of the Mississippi River. Pawtucket families who were interned with Nipmuc, Pocumtuc, and Mahican families at the Stockbridge, Brotherton, and Schaghticoke reservations were forced to move to the Stockbridge-Munsee reservation in Wisconsin, which still exists. Pawtucket interned with Mohawk have living descendants on the Iroquois reservations in upstate New York and Canada. The Pawtucket do not exist in any organized band, tribe, or nation today, but many Wampanoag, Nipmuck, and Massachusett tribes claim Pawtucket ancestry.

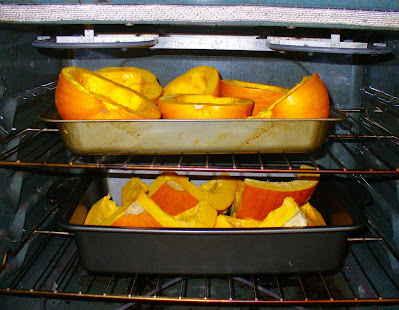

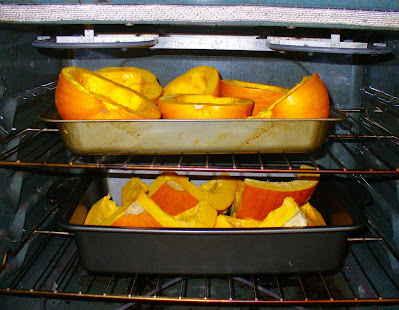

3. Cook the pumpkins: The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving.

The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving.

To cook, I chop each pumpkin in half, clean out the centers, and bake them at 250ºF until they were soft. Then I scoop them out of the skins and put the pumpkin in containers in the refrigerator or freezer.

Pumpkins have been grown in North America for five thousand years; first domesticated in Central America, they were eventually brought to North America, where they came to form a part of the diet of the Indigenous People. Native Americans enjoyed the inner pulp of the pumpkin baked, boiled,

roasted and dried. They added the blossoms to soups, turned

dried pumpkin pieces into rich flour, and ate the seeds as a

tasty snack. They also dried strips of pumpkin and wove them into mats.

The Puritans also used pumpkins. The pumpkin was actually brought over to Europe into France after Columbus’ voyage in the sixteenth century, and sometime after introduced to England, so the pilgrims to North America were already familiar with them.

Puritans maintained a modest lifestyle, and opposed the excess of English feasting and drinking and throwing away leftovers. They associated vegetables with virtue and the pumpkin in particular represented a humbleness. It kept well, was from the earth, could be used in abundant ways, and all parts were useful, from skin to seed to pulp. As one of the major chroniclers of early New England, Edward Johnson, said in 1654: “Let no man make a jest at pumpkins, for with this fruit the Lord was pleased to feed his people.”

The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving.

The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving.

No comments:

Post a Comment