The U.S. Department of the Interior Indian Affairs theme this year is Weaving together our past, present and future. "We will focus on the failed policies of the past with a focus on the Federal Indian Boarding Schools and moving into the present and the work being done to address the intergenerational trauma Native people still face. In partnership with the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Smithsonian Institution, we are working to record the lasting impacts of that era and share that information with all Americans. As Indigenous people, our past, present and future are all connected."

Agenda:

Before contact with Europeans, the Kalapuyan population may have numbered as many as 15,000 people. With the arrival of Euro-Americans came also catastrophic epidemics of malaria, smallpox, and other diseases. Some accounts record tales of entire villages empty of people. By 1849 the population of the Kalapuyan tribes had dropped to around 600.

Over the following months, the militia had no luck forcing the Cayuse to give up the wanted men, and the militia's military campaign ended in late summer 1848. Eventually, Joseph Lane, governor of the newly created Oregon Territory, persuaded friendly Cayuse to offer five individuals for trial. By April 1850, Oregon officials had these 5 in custody, and they were tried and hanged.

The Cayuse War started three decades of conflict with Natives in Oregon.

Chapter 2 is Grateful Living as a Way of Life. It covers the five guiding principles of Brother David's teaching.

The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving.

The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving.

The Puritans also used pumpkins. The pumpkin was actually brought over to Europe into France after Columbus’ voyage in the sixteenth century, and sometime after introduced to England, so the pilgrims to North America were already familiar with them.

Puritans maintained a modest lifestyle, and opposed the excess of English feasting and drinking and throwing away leftovers. They associated vegetables with virtue and the pumpkin in particular represented a humbleness. It kept well, was from the earth, could be used in abundant ways, and all parts were useful, from skin to seed to pulp. As one of the major chroniclers of early New England, Edward Johnson, said in 1654: “Let no man make a jest at pumpkins, for with this fruit the Lord was pleased to feed his people.”

1. Anti-racism intentions

2. The Kalapuyans

2. The Kalapuyans

3. Read "Wake Up Grateful"

4. Cook the pumpkins

4. Cook the pumpkins

1. Anti-racism intentions:

I have enjoyed studying my ancestry over the years, but I'm well aware of the inherent white privilege of this study. This document, Genealogy and anti-racism by Diane Kenaston, asks the question, "So, are there ways for white people to act as anti-racist allies while exploring our own white ancestry?" She could be writing my own thoughts here:"Through ancestors' participation in the DAR, I have family trees going back to the 1700s ---- and the knowledge that the DAR was formed for explicitly racist reasons. Through ancestors' ability to purchase homes, attend institutions of higher education, and transfer wealth to their descendants, I have paper trails. ... Local, state, and federal governments have valued keeping my ancestors’ records and writing down their names. Some of my ancestors benefited from the Homestead Act, in which the U.S. government transferred to white citizens land stolen from indigenous peoples. Even for those who didn’t directly apply for land under the Homestead Act, by migrating to these shores, my ancestors participated in what is known as “settler colonialism” --- deliberately replacing native peoples with new settlers."

This document has some great suggestions for action, including sections on confronting slavery, confronting settler colonialism and homesteading, and confronting immigration restrictions.

So I set another intention:

I intend to find out whose traditional territory my ancestors were on, learn more about the people, history, and contemporary concerns of these indigenous communities, and share that information with my family, because this is one way I can dismantle the systems of racism.

2. The Kalapuyans:

One of the best ways to dismantle stereotypes and counteract the mythology of Thanksgiving is to acknowledge the actual First People of the place you live, and know their history. To that end I decided to research my ancestors who arrived in Oregon in the late 1800's and the Native People who lived here first.The place we know today as Oregon was the home of many, many tribes of indigenous people prior to European exploration and settlement. Native peoples have lived in the area since 8000 BCE. Like most parts of the country, Native People here were decimated mostly by disease. The first smallpox outbreak among Oregon’s indigenous people was in 1775, and the second was in 1801.

Prior to 1842, the land of the Willamette Valley belonged to the Kalapuya tribe, which consisted of nineteen tribes in three distinct areas of Oregon: north, south and central. Their major tribes were the Tualatin, Yamhill, and Ahantchuyuk at the north, the Santiam, Luckamiute, Tekopa, Chenapinefu in the central valley and the Chemapho, Chelamela, Chafin, Peyu (Mohawk), and Winefelly in the southern Willamette Valley. The most southern, Yoncalla, had a village on the Row River and villages in the Umpqua Valley and so lived in both valleys. The major tribal territories were divided by the Willamette River and its tributaries.

The early Kalapuyans did not belong to a single homogeneous tribal entity, but rather to multiple autonomous subdivisions speaking three closely related languages which may have been mutually intelligible. Each of these bands occupied specific areas along the Willamette River and its tributaries. The various Kalapuyan bands were hunter-gatherers who fished, hunted, and gathered nuts, berries and other fruits and roots. The tribe made use of obsidian (obtained from the volcanic Cascade ranges to the east) to fashion sharp and effective arrowheads and spear tips. (Former on Kalapuyan lifestyles, see the Lane Library article.)

Before contact with Europeans, the Kalapuyan population may have numbered as many as 15,000 people. With the arrival of Euro-Americans came also catastrophic epidemics of malaria, smallpox, and other diseases. Some accounts record tales of entire villages empty of people. By 1849 the population of the Kalapuyan tribes had dropped to around 600.

The first major and ongoing conflict between Native groups and white resettlers in Oregon was a direct consequence of the murders by Cayuse tribesmen of 13 missionaries at the Whitmans’ mission near present-day Walla Walla, Washington, on November 29, 1847. The Cayuse War was a nearly two-year campaign that was a mixture of military actions, peace negotiations, and the pursuit of those who had killed the missionaries.

In 1850 the Oregon Donation Land Act was enacted by the U.S. Congress to promote homestead settlement in the Oregon Territory. It granted free land to “Whites and half-breed Indians” in the Oregon Territory. In 1851 the discovery of gold in Southern Oregon brought a surge of miners and settlers, igniting years of bloody conflicts called the Rogue River Indian Wars.

On April 12, 1851, at the Santiam Treaty Council in Champoeg, Oregon Territory, the leaders of the Santiam Kalapuya tribe expressed strong opinions over their desire to remain on their traditional territory, between the forks of the Santiam River. The other Kalapuyan tribes followed their lead and proposed the same deal for their area. The following round of treaty cycles in 1851 were never ratified due to the proposed placement of Indian reservations inside the Willamette Valley and the fact that the whole valley was fully claimed by white Americans by 1851.

In the Willamette Valley Treaty at Dayton, Oregon, concluded on January 22, 1855, the Kalapuyans and other tribes of the Willamette valley, including Molallans, Clackamas and tribes on the Columbia- Cascades, Multnomah, and others, ceded the entire drainage area of the Willamette River, and were promised a permanent reservation, money, annuities for food, clothing, education, and health care and safety and security away from the white Americans. They agreed to remove to a permanent reservation and were temporarily relocated to ten temporary reservations on settler donation land claims. Between February and May 1856 they were removed to Grand Ronde Indian Reservation.

Life at Grand Ronde was difficult for the tribes, with at least 27 tribes removed to the reservation. The reservation was managed by Indian agents assigned by the Superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon. Fort Yamhill was established with a detachment of dragoons, to defray possible attacks on the tribes by white Americans, many of whom professed a desire to “exterminate all Indians,” and to be a deterrent against Indian outbreaks or Native people leaving the reservation. It was illegal for native peoples to be off reservation without a pass, as they were not U.S. citizens until 1924 when the Native American Citizenship Act was passed.

Schools were established at Grand Ronde, Day schools paid for through treaty annuities, and boarding schools managed and taught by first the Protestant missionaries and later the St. Michael’s boarding school established by the Catholic Church under government auspices. The day school and an on-reservation boarding school, were established to assimilate Native children to American cultures, and at the boarding schools children had to stay throughout the school year. It was through education that the Indian Agents sought to carry out federal policies of assimilation for children.

For adults assimilation was carried out by impressing upon them to become farmers and to convert to Christianity through the government-sanctioned missionary churches.

Sanitation and health care at the reservation was poor and mortality was high. The U.S. did not keep it's promises of money, food, or clothing until 1889, and so for the years 1856 to 1889 the native people lived in extreme poverty, completely dependent on government supplies, only gaining some land in the 1870s, and becoming self-sufficient for many by 1880.

By 1900 only about 300 remained of the original 1,200 people that had been removed to the reservation. The population reduction was caused in part by poor health care and poor nutrition, but the culture of poverty at the reservation caused many to leave and never return.

All of the bands and tribes of the Kalapuyans were terminated at the Grand Ronde Reservation when their treaties were terminated in 1954 along with all other Western Oregon tribes, in the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act. The Kalapuya treaties were restored through the restoration bills of the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz (1977) and Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon (1983).

The descendants of the Kalapuyan tribes and bands married extensively into other tribes throughout the Northwest and within the reservation, and most now have multiple native ancestries. The majority of Kalapuyan descendants are enrolled at The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community. There are an estimated 4,000 Kalapuyan descendants.

3. Read "Wake Up Grateful":

I've been reading this book by Kristi Nelson (2020), with the sub-title "The Transformative Practice of Taking Nothing for Granted". She explains how she met Brother David Steindl-Rast, and eventually began to work with him on The Network for Grateful Living website, and that this book is a guidebook based on Brother David's teachings.

Chapter 2 is Grateful Living as a Way of Life. It covers the five guiding principles of Brother David's teaching.

The third principle is The Ordinary is Extraordinary. One of the easiest pathways to a sense of abundance is to savor and celebrate the ordinary. "What's truly ordinary anyway? Is there such a thing as an ordinary flower? Sunrise? Book? Bird? Are there ordinary days?"

One practice she recommends is to pause throughout the day to notice each "ordinary" item: a toothbrush, fork, pillow, or pen - and allow it to reveal its extra-ordinariness, its beauty and ingenuity. Imagine what your life might be like without it. Consider what went into making it and all the ecosystems involved in bringing you this gift.

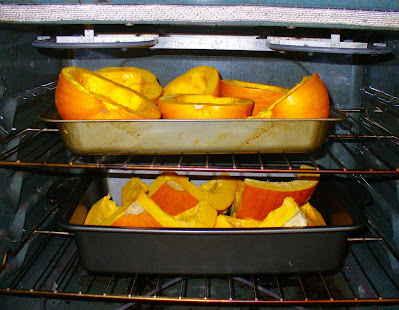

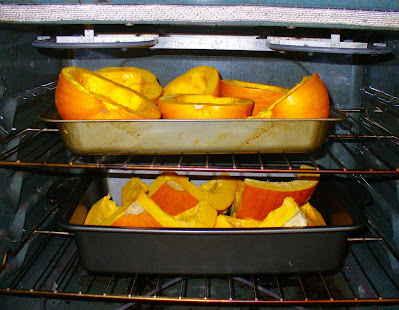

4. Cook the pumpkins:

The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving.

The secret to good pumpkin pie is to use fresh pumpkin. I've got a few pie pumpkins that I need to process and cook, so they are ready for pie making by Thanksgiving. To cook, I chop each pumpkin in half, clean out the centers, and bake them at 250ºF until they were soft. Then I scoop them out of the skins and put the pumpkin in containers in the refrigerator or freezer.

Pumpkins have been grown in North America for five thousand years; first domesticated in Central America, they were eventually brought to North America, where they came to form a part of the diet of the Indigenous People. Native Americans enjoyed the inner pulp of the pumpkin baked, boiled,

roasted and dried. They added the blossoms to soups, turned

dried pumpkin pieces into rich flour, and ate the seeds as a

tasty snack. They also dried strips of pumpkin and wove them into mats.

roasted and dried. They added the blossoms to soups, turned

dried pumpkin pieces into rich flour, and ate the seeds as a

tasty snack. They also dried strips of pumpkin and wove them into mats.

The Puritans also used pumpkins. The pumpkin was actually brought over to Europe into France after Columbus’ voyage in the sixteenth century, and sometime after introduced to England, so the pilgrims to North America were already familiar with them.

Puritans maintained a modest lifestyle, and opposed the excess of English feasting and drinking and throwing away leftovers. They associated vegetables with virtue and the pumpkin in particular represented a humbleness. It kept well, was from the earth, could be used in abundant ways, and all parts were useful, from skin to seed to pulp. As one of the major chroniclers of early New England, Edward Johnson, said in 1654: “Let no man make a jest at pumpkins, for with this fruit the Lord was pleased to feed his people.”

No comments:

Post a Comment